Dr. Hartmut Schorrig, www.vishia.org, 2020-11-13 / 2022-04-22

See also

1. Approach

Processors in Embedded often run algorithm in very short sampling time. For example 50 µs, 10 µs.

It is possible because the processors are fast (40 MHz clock, 200 MHz clock) and the algorithm are short and physical affine (Analog values, fast communication).

It is necessary because some controlling tasks need a very high sampling rate, high timing resolution and a less dead time, especially for controlling of electrical signals.

For such step times of controlling algorithm a Real Time Operation System (RTOS) is a too high effort and it does not guarantee thread switches in such a less time. Also if the RTOS thread scheduler by itself may guarantee a thread switching in less than 1 µs, there are no guarantee that the other user thread blocks the switching because of some locked data etc (mutex).

The execution of essential parts of the application immediately in a hardware interrupt is a simple and universally known solution, used since the beginning of Microprocessor usage, but rarely discussed as principle.

Such a system can have more interrupts, and a back loop. In this article it is favored and presented to have only one interrupt for the fast cyclically stuff. The special feature is that the back loop is used in a way to execute slower tasks quasi-parallel, but without thread scheduling, in particular without context switching (changing the stack pointer). This allows slower tasks to run in the back loop. It is applicable also for cheap controller. For that a link to a zip file with a MSP430 project (Texas Instruments, common known, 16 bit, 12..20 MHz) is linked here as demonstration.

2. Data exchange, mutex in interrupts

2.1. Compare situation with mutual exclusion access in threads of a RTOS

In a RTOS usual a lock algorithm is used to assure mutal exclusion on the access:

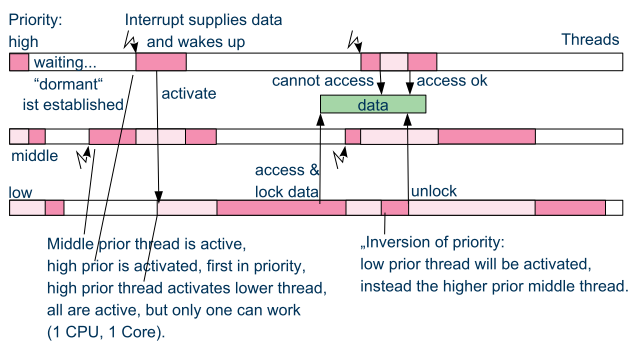

The image above shows the typical situation using a Real Time Operation System (RTOS).

2.2. What is possible in interrupt routines?

Using interrupts this cannot be done in this way: If the interrupt should write data and the lock is active, it is not possible to switch to the locking thread and then back to the interrupt. It means, this schema cannot be used.

What is possible?

-

A) Try to think about data exchange without mutex. Is it possible to organize?

-

B) Interrupt disable range in the backloop for mutual exclusion to data.

-

C) Usage of compare and swap access.

2.3. A) Keep it simple and separated

The case A) may be possible, think about and keep it simple. If you have a ring buffer which is only written in interrupt, and read out in the backloop, you can increment the write pointer in the interrupt, and the independent read pointer in the backloop:

//in interrupt:

int wr1 = this->wr +1;

if(wr1 >= this->size) { wr1 = 0; } //wraps

if(wr1 != this.rd) { //if equal, then the buffer is full.

data[this->wr] = value; //store data from interrupt

this->wr = wr1;

}

//in backloop

if(this->rd != this.wr) {

value = data[this->rd];

this->rd +=1;

}

It is very simple because the sensible indices to the data are separated.

The value of this→rd is never changed in the interrupt, so the backloop have the full control.

It is tested in interrupt, but the new value is set only after the access. This order is important.

But as you can see in this example, writing new data to the interrupt is blocked when the queue is full, because: The processing (reading) thread is too slow. This is a problem of the whole application. It should be clarified why the processing is too slow, or whether new data should not be transferred or older data should be removed from the queue.

2.4. B) Using disable_Interrupt()

If the same algorithm, a ring buffer, can be written in more as one interrupt, or in the backloop too, this is a more complex requirement. Such can be necessary if the ring buffer stores events (for state machine, for specific execution control), and the events can be written in the ring buffer both in interrupt and in the backloop. Then the problem is given:

//in interrupt:

int wr1 = this->wr +1;

if(wr1 >= this->size) { wr1 = 0; } //wraps

if(wr1 != this.rd) { //if equal, then the buffer is full.

//<<=== if another interrupt have done the same, the data position is used twice.

data[this->wr] = value; //store data from interrupt

this->wr = wr1;

}

Using solution B) the whole write access should be wrapped with

disable_Interrupt(); .... enable_Interrupt();

in all interrupts and the backloop except the highest interrupt. If the access (write data in the buffer, more as a simple float) needs more time, the highest may be fast interrupt may be delayed. It produces a 'jitter' for interrupt processing. If the system has a very fast interrupt cycle (10 µs) with a tightly calculated remaining computing time or a necessary real timing in the execution of the interrupt (it may be so for special requirements) and the time to write data in the queue is greater than about 2..5 µs, it does not work! Generally the disable-interrupt time should be as less as possible.

The disable_Interrupt() and enable_Interrupt() are special machine instructions, for some processors only possible to use in the so named 'kernel mode'.

2.5. C) atomic compare and swap

The 'compare and swap' methodology is possible to use both in interrupts and in multithreading. In interrupts it is the only one possible solution to organize a mutual exclusion (beside disabling), for multithreading it is more fast than using semaphores. But 'compare and swap' can only be used if only one cell in RAM is the candidate of mutex. This is an important restriction, but some algorithm especially for container handling are possible with well-thouht-out usage of dedicate variables for mutex with 'compare and swap'.

'compare and swap' was introduced with Java-5 in about 2004. The basic is a machine instruction which was introduced already with the Intel 486 processor family:

lock cmpxchg addr, expect

See https://software.intel.com/content/www/us/en/develop/download/intel-64-and-ia-32-architectures-sdm-combined-volumes-1-2a-2b-2c-2d-3a-3b-3c-3d-and-4.html, then in the downloaded pdf page Vol.2A 3/189 or search the instruction CMPXCHG.

The specific of the atomic compare and swap statement is: * The whole operation is done not interruptable. * Writing a new value on a given address location will only be executed if an expected value is present there. * The existing value on the memory address is always read, so that a comparison can be done afterwards whether it is the new value. If not, this value can be used for the next access immediately without a second read operation. That’s why "swap". * It is also important that this command accesses actual memory and not just cached data. This ensures that it works correctly in multicore environments. Other cores are also blocked per hardware for the access to exact this memory location, and after the access the maybe changed data are present also for the other cores (presumed, they use also the atomic compare and swap instruction). It means for multicore processors this compare and swap instruction is basically, and existing. Because the 'compare and swap' instruction is processor specific, it should be organized in a special OSAL or HAL adaption layer ('Operation System Adaption Layer' or 'Hardware Adaption Layer').

A simple processors often used in embedded control may not have such a compare and swap instruction nor have multiple cores. But the compare and swap technology is nevertheless sensitive or essential between interrupts and the back loop or for different interrupts. The solution for that is: Using disable and enable interrupt for a fast sequence of separated machine code statements. Hence this statements are atomic, not interruptable. The resulting functionality is the same as given with a processor specific compare and swap atomic instruction.

Here as example shown for Texas Instruments TMS320C28 series:

static inline int32 compareAndSwap_AtomicInt32 (

int32 volatile* reference, int32 expect, int32 update) {

__asm(" setc INTM");

int32 read = *reference;

if(read == expect) {

*reference = update;

}

__asm(" clrc INTM");

return read;

}

It is implemented in C language (or C++) but with special assembler instructions: The important thing is the interrupt disabling and enabling. It means the approach B) is used (chapter above), but not in the users algorithm, instead in a 'system routine' or OSAL or HAL layer. The application source uses only the common present `compareAndSwap_AtomicInt… ` invocation which is adapted for gcc on Intel-based PC, for Windows etc. in form:

int32 compareAndSwap_AtomicInt32(int32 volatile* reference, int32 expect, int32 update) {

return InterlockedCompareExchange((uint32*)reference, (uint32)update, (uint32)expect);

}

and for GCC for Intel based execution:

int32 compareAndSwap_AtomicInt32(int32 volatile* reference, int32 expect, int32 update)

{ __typeof (*reference) ret;

__asm __volatile ( "lock cmpxchgl %2, %1"

: "=a" (ret), "=m" (*reference)

: "r" (update), "m" (*reference), "0" (expect));

return ret;

}

All three routines have the same signature, they are equal for usage in the application. The implementations are different due to the platform.

If an user’s algorithm is written with 'compare and swap', for example and especially using common container library routines, it can be used without adaption both in interrupts and its backloop and in multithreading in a RTOS. That’s the advantage.

'compare and swap' is slightly slower (more calculation time) in comparison with a simple disable interrupt part. The difference is given, but is is less. A fast interrupt as usual the highest priority, it can spare the encapsulation, execute immediately. No one interrupts the access, hence it is atomic too. In lower prior interrupts the minor increased calculation time may be admissible.

2.6. Application example of using atomic compare and swap

Let’s use the ring buffer example above, but now with several interrupts or writing in the back loop. It can be applied to a message queue for event processing, for example.

The here shown sources are the original in emC/Base/RingBuffer_emC.h.

Firstly look on the data definition for a RingBuffer management:

typedef struct RingBuffer_emC_T {

union{ObjectJc obj; } base;

/**Number of entries in the Ringbuffer struct, range of the index 0 till nrofEntries -1.

* Note: The size of the queue is limited to 65535 entries because of int16 usage, seems to be really enough.

*/

uint16 nrofEntries;

/**A counter to detect access. Incremented on any change.

* Also int16 because of a proper memory layout for alignment see www.vishia/emc/html/Base/int_pack_endian.html

*/

int16 volatile ctModify;

/**Index to read from queue.array[thiz->ixRd].

* ** If ixRd==ixWr, then the queue is empty.

* ** If queue.array[thiz->ixRd].evIdent ==0 (invalid), a write is pending on this position

* and the queue is empty yet at the moment.

* ** If ixRd!=ixWr and queue.array[thiz->ixRd].evIdent !=0, it is the current entry.

* ** ixRd can be increment without lock.

* But use the access operations next_RingBuffer_emC(...) and quitNext_RingBuffer_emC(...)

*/

int volatile ixRd; //use signed because difference building.

/**Index of the next write position.

* ** if (ixWr+1) modulo sizeQueue == ixRd, then the queue is full. Add will be prevented.

* **+ It conclusion, the last position in queue.array[..] will never be used, a really little disadvantage of this simple rule.

* ** ixWr is firstly incremented with atomicAccess to get a reservation for this position in ixWrCurr

* ** after them the position should be filled and then marked as valid.

* Note that the int data type for the indices is the platform-intrinsic type of memory access,

* Usual better for compareAndSwap. The really used range is usual less, int16 may be sufficient.

*/

int volatile ixWr; //+rd and wr-pointer

/**Only for debug, statistic runtime analyse, max repeat count of compareAndSwap loop. */

int repeatCtMax;

} RingBuffer_emC_s;

There are some comments also in the source:

The buffer itself with any specific type for the entries is located outside, extra, not here. This class manages only the indices for reading and writing, currently from 0 till the max value, as the index to access the array for the data used as ring buffer information.

This management functionality can be used either for exactly one writing source, using addSingle_RingBuffer_emC(…) or from more as one thread or interrupt which writes data, using add_RingBuffer_emC(…). This last operation works with atomic compare and swap, also applicable for simple controller, see www.vishia/emc/html/Base/Intr_vsRTOS.html With this second variant it is possible for example for an message queue for event processing to write events in different interrupts as also in the back loop, or of course using a RTOS with multi threading.

But the reading source should be only one thread. This is typically for a message queue which can be written from different sources but processed from only one thread. It is also typically for and data processing, if the data comes from several sources (several interrupts or threads) and should be processed even in exactly one thread or in the back loop for an interrupt using system without RTOS. <br> The following property is recommended: An active entry in the array for the RingBuffer data should be marked as "valid" or not "valid". This is necessary because for multi threading for writing. Only with this rule atomic compare and swap can be used because it needs one operation to set. It is also more simple for a single writing thread or interrupt. Elsewhere a second index for 'available data' will be necessary.

The writing thread gets the next free entry, and immediately this entry is marked as used in this ringbuffer structure because the writing index is incremented. That is important because the next access can get immediately the next writing position.

Now, on read access, the location is marked as "written" from the view point of this index management structure. But the data may not be written till now if the read access is executed immediately. In a system: Writing in interrupt, process in the back loop, of course the writing may be done completely in the interrupt before finish the interrupt and switch to the back loop. Then it is not a problem. But if multiple threads access and the read access may be higher prior, or the writing needs more time, for example more as one interrupt cycle, then this problem is present. That’s why firstly the data for the entry should be written in its intrinsic timing. The last action of writing should be: declare the data as valid.

Then a read access get the index, to read, but detect, there are not valid data. This is to do in the using algorithm, for example even in the message queue functionality. Then the read access should try get data later. That’s why getting the read index is divided in two operations:

-

next_RingBuffer_emC(…) to get the next read index.

-

… test the location whether the data are valid

-

… set the processed data as 'invalid' for a next usage.

-

quitNext_RingBuffer_emC(…) to advertise that the postion was used, only if data were valid.

In that manner the next call of next_RingBuffer_emC(…) returns the same position again to test for valid data if quitNext_RingBuffer_emC(…) was not invoked.

The simplest possibility to mark invalid is a null pointer in the ring buffer (pointer) array. If the ring buffer array is a array of embedded struct members, then the validy should be marked in a special kind clarified by usage.

Now look on the add_RingBuffer_emC(…) operation which uses the compare and swap

/**Adds an entry to the ring buffer with atomic lockfree mutex.

* This operation can be invoked from any thread or interrupt.

* It works with atomic cmpAndSwap to access.

* It returns the current ixWr if a new ixWr position is possible

* but has set the new ixWr position for a next add access in another thread.

*

* @return the index to write in the application definied ring buffer array.

* or -1 if no more space is in the queue.

* This is if the new ixWr position would touch the ixRd position

*/

static inline int add_RingBuffer_emC ( RingBuffer_emC_s* thiz ) {

#ifndef NO_PARSE_ZbnfCheader

#ifdef DISABLE_INTR_POSSIBLE_emC

disable_interrupt_emC();

int ixWr = addSingle_RingBuffer_emC(thiz);

enable_interrupt_emC();

return ixWr;

#else

int repeatCt = 0;

int volatile* ptr = &thiz->ixWr; //address of the ixWr

int ixWrLast = thiz->ixWr; //The position where the event should be written to the queue.

int ixWrExpect; //to compare

do {

ixWrExpect = ixWrLast;

int ixWrNext = ixWrLast + 1;

if(ixWrNext >= thiz->nrofEntries) { ixWrNext =0; } //modulo

if(ixWrNext == thiz->ixRd) {

return -1; //RETURN: no more space in queue

}

TEST_INTR1_RingBuffer_emC //This macro is normally empty, only used for specific test to interrupt the access.

ixWrLast = compareAndSwap_AtomicInt(ptr, ixWrExpect, ixWrNext); //set for next access.

} while( ixWrLast != ixWrExpect && ++repeatCt < 1000); //repeat if another thread has changed thiz->ixWr.

if(repeatCt >=1000) {

//it is a problem of thread workload, compareAndSet does not work.

THROW_s0n(IllegalStateException, "thread compareAndSwap problem", 0, 0);

return -1; //RETURN for non-exception handling, THROW writes a log entry only.

}

if(thiz->repeatCtMax < repeatCt) { thiz->repeatCtMax = repeatCt; }

#endif

//the ixWrCurr is proper for this entry, another thread may incr thiz->ixWr meanwhile

//but the other thread uses the position after.

return ixWrLast;

#endif//NO_PARSE_ZbnfCheader

}

Somewhat is already explained in the comment in the source. Additionally the following:

-

If the compiler switch

DISABLE_INTR_POSSIBLE_emCis set, then instead this routine the more simpleaddSingle_RingBuffer_emC(…)is called under interrupt disabling. This is the first choice for a simple processor. It does the same and it is proper in multithreading because the whole non atomic operation cannot be interrupted. Under this compiler switch also thedisable…andenable_interrupt_emC()should be defined. -

It means this algorithm with compareAndSwap is usual firstly for a system with RTOS, because for that usual manually disable/enable interrupt is not possible. But it can also be used in a simple system because / if

compareAndSwap_AtomicInt(…)is emulated, see above. -

As you see, typical for the compare and swap approach, the access is repeated if it was not successful. Now a principled thinking may flare up: What about if this situation is frequently repeated. The answer is: This is a mistake in software, for example read or compare the faulty data. Or it is a failure of the RAM access in hardware. In practice it cannot be occur because:

-

If another thread interrupts one time in this short time spread, then this loop is repeated one time.

-

The coincidence that the same thread interrupts again in this short time is exact 0, because the same thread cannot access shortly twice.

-

But of course the coincidence that another thread interrupts also, is given. It is less, but given.

-

In conclusion, the maximal number of repeating depends only on the number of threads which accesses this same data. And this number is usual less, 2, 3 till 10 or a little bit more in a complex system. But the number of 1000 is never reached if all is proper.

-

The review of the repetition is carried out only in principle, or even to detect software mistakes. Any loop should be terminated by a counter.

-

The

THROW_s0n(…)on this error situation is also in principle, even to handle a software error. For a fast execution the exception handling can be switched off (first idea), but this statement is anyway never reached if the software is proper. An exception handling is also possible for interrupts, especially in development phases, see ThCxtExc_emC.html.

-

The coincidence that one or more threads interrupts this access loop is less.

It depends on the cycle time of the access in comparison to the time of the access between reading the content

and execution of the compare and swap, it is able to calculate.

It means that the calculation time of this access in the non interrupted situation is less.

Using a semaphore mechanism (mutex) needs a very more higher calculation time because the thread scheduler should manage

some thread tables etc. That is the advantage of compare and swap

and exactly thats why it was introduced also in Java in ~2004 because Java is frequently used for server programming

with many less threads or tasks. In Java there is for example a ConcurrentLinkedQueue where this is used.

The usage of this RingBuffer manager in an event queue is documented in …. TODO, not in this article (too much), but it is applicable for interrupts also.

3. Organization of more as one task in the back loop

In a simple system with interrupt(s) and the back loop, in the back loop some things can be executed. It is a quest of organization. For example interrupts are only responsible for the immediate handling of hardware accesses, and especially for a fast cyclically step operation (for controlling approaches) in range 20..50..µs, 1 ms. All slow cyclically things can be done in the back loop (1 ms and greater). This time values can be also true on relative slow processors, for example MSP430 from Texas Instruments.

How should it be organized? Any specific manual programming is usual and possible, but inflexible. A system is better.

One of the basic ideas to organize the back loop is:

-

Any particular action should have a short execution time. If you have time cycle ranges in 1 ms, then the execution time on one action should be < 1 ms. It should be checked and asserted.

-

You can divide a longer algorithm in steps. Between steps the data are stored in the associated structure, not in the stack. Hence the operation should be finished and recalled later or maybe immediately for continue. On immediately call also another action can be done firstly if it has a priority.

This is similar as event processing with state charts. One event execution should be also atomic and short.

A Real time Operation System with concurrently long running threads with wait states is the other, opposite concept.

3.1. A simple task system without message queue

If a user’s algorithm should run a longer time and other algorithm (threads) should be executed a longer time concurrently, only a RTOS can help. But if the user’s algorithm can be dissipate in short actions, any of it can be executed one after another (non preemptive), together with other short actions, a simple task system based on events is possible.

A task is presented by a short routine to execute.

Is a message (or event-) queue necessary to organize the task execution?

If the system knows less event types, any event can have its EventTask_emC instance.

In this instance the occurrence of the event is marked, also with a time for execution:

//file: src_emC/emC/Base/EventTask_emC.h:

/**The variable data for a task which can be activated.

* This is the event instance which can used immediately to poll in a simple task scheduler.

*

* The variable data are referenced from a const [[struct TaskConstData_emC_T]].

* Then one const TaskConstData_emC refers exact one instance of this struct.

* Activating the event is possible with a given time and priority.

* Hence this data should be referenced and used only via the const TaskConstData_emC instance.

*/

typedef struct EventTask_emC_T {

/**A priority counter, up counting, 0 = not activated, >0 should be activated, higher number <=126 is prior.

* With that some events can be designated with an execution priority.

* It enables another principle than First in First out.

*/

uint8 ctPriority;

/**The priotity use bits 6..0, max value 126*/

#define mPrio_EventTask_emC 0x7f

/**If this bit is set, the instance is of type EventTaskTime_emC_s, with time. */

#define mTime_EventTask_emC 0x80

} EventTask_emC_s;

This structure can be checked in the back loop, all instances one after another. It contains only one data element: priority. If this cell is ==0 the task is not activated. If you have more tasks activated similar, then the priority decides which is started. But also, the priority will be increassed for that tasks which are not started yet. Resulting, it should be executed anyway later with the higher priority, though the system may be overloaded by firstly more priority tasks, if there are too many tasks activated for the back loop.

This last point can be important: If you have one task for monitoring with a low priority, and some other tasks which are activated too many times, because of an software mistake during development, then the monitor task should be work anyway, maybe delayed. So you can access your system, detect and fix the behavior. In the other case, the higher prior faulty tasks blocks the whole system.

For a really simple system only one bit in a bit field is enough to mark activating.

There is a second approach, start with time:

//file: src_emC/emC/Base/EventTask_emC.h:

/**The variable data for a task which can be activated.

* This is the event instance which can used immediately to poll in a simple task scheduler.

*

* The variable data are referenced from a const [[struct TaskConstData_emC_T]].

* Then one const TaskConstData_emC refers exact one instance of this struct.

* Activating the event is possible with a given time and priority.

* Hence this data should be referenced and used only via the const TaskConstData_emC instance.

*/

typedef struct EventTaskTime_emC_T {

/**Basic class with priority, same behavior. */

EventTask_emC_s prio;

/**A short time from which this task should be executed.

* This short time should be system width related to a wrapping short time counter

* which allows also a relation to an absolute time.

* But the short time is more simple to execute.

* This cell is not counting, it is not a delay.

* It is a given time in the short time system to clarify when to start the task.

* Therewith cyclically tasks are possible.

*/

int timeExec;

} EventTaskTime_emC_s;

As you see in the definition this struct enhances the EventTask_emC_s, it is inheritance in ObjOriented kind.

It means both data can be used similar and mixed.

The idea is, a task is activated to start but later, either with a delay or cyclically.

You have three operations to activate a task which can be called either in interrupt or in a back loop operation, or of course also in any thread of an RTOS:

//file: src_emC/emC/Base/EventTask_emC.h:

/**Activates the entry if it is free.

* If the event is not free, in use, queued resp. activated this routine does nothing but returns false.

* @param priority higher value till 254 means, execute it prior.

* But the priority will be counted up on each test.

* @return true if activated, false if it is activated (in use) already.

*/

static inline bool activate_EventTask_emC(EventTask_emC_s* thiz, uint priority) {

if(thiz->ctPriority == 0) {

ASSERT_emC(priority < mPrio_EventTask_emC, "priority faulty", 0, 0);

thiz->ctPriority = priority;

return true;

} else {

return false; // it is already activated.

}

}

This is the activation with priority immediately without time, using the basic structure.

/**Activates the entry to a dedicated time if it is free.

* If the event is not free, in use, queued resp. activated this routine does nothing but returns false.

* Generally: The taks is started if the current time, incremented by the fast cyclically interrupt,

* is greater or equal the registered time. It means if the registered time is in the past

* alreday while calling this routine, the activating will be done immediately (depending on priority).

* The quest past or future is determined by the sign of the difference between the current time,

* gotten via timeShortStepCycle_emC() minus the here registered time. If the difference is positive,

* the time is expired. A negativ difference means, future. Because of the wrapping property

* the half period can be used. A time difference > half wrapping period is not possible.

* The wrapping point itself is not a problem because differences are built without overflow in C(++) language,

* it is anyway correct for signed integer.

* @param priority higher value till 126 means, execute it prior.

* But the priority will be counted up on each test.

* @param time start time related to the global interrupt cycle time.

* @return true if activated, false if it is activated (in use) already.

*/

static inline bool activate_EventTaskTime_emC(EventTaskTime_emC_s* thiz, uint priority, int time) {

if(thiz->prio.ctPriority == 0) {

ASSERT_emC(priority < mPrio_EventTask_emC, "priority faulty", 0, 0);

thiz->timeExec = time;

thiz->prio.ctPriority = priority | mTime_EventTask_emC;

return true;

} else {

return false; // it is already activated.

}

}

This activation presumes the structure with time.

The time itself is a wrapping time which should be determined by the fastest interrupt cycle.

If the fastest interrupt cycle is for example 100 µs, then an int value with 16 bit of a cheep controller

has a time range till 3.25 seconds (used only the positive half).

The time stamp can be synchronized also to an absolute time, for example by embedding of the controller in a network,

or using a timer module from GPS or such.

The routine to get the time is defined in emC/Base/Time_emC.h as:

/**Returns a wrapping short time counting with the fast interrupt cycle. * This operation must be defined in a target- and application specific way, * it means usual in the organization of main, interrupts and threads. */ int timeShortStepCycle_emC ( );

Some modifications for the time:

/**Activates the entry with a delay due to the current time if it is free.

* @param priority higher value till 126 means, execute it prior.

* But the priority will be counted up on each test.

* @param delay start time delay related to the global interrupt cycle time.

* @return true if activated, false if it is activated (in use) already.

*/

static inline bool activateDelayed_EventTaskTime_emC(EventTaskTime_emC_s* thiz, uint priority, int delay) {

if(thiz->prio.ctPriority == 0) {

ASSERT_emC(priority < mPrio_EventTask_emC, "priority faulty", 0, 0);

thiz->timeExec = timeShortStepCycle_emC() + delay;

thiz->prio.ctPriority = priority | mTime_EventTask_emC;

return true;

} else {

return false; // it is already activated.

}

}

Here the time is not absolute related to the timeShortStepCycle_emC() but given as delay from the current time,

more simple in usage. For example in an interrupt a execution of a operation in the back loop can be started with a dedicated delay.

/**Activates the entry to a next cycle time if it is free.

* @param priority higher value till 126 means, execute it prior.

* But the priority will be counted up on each test.

* @param cyclediff start time added to the last start time. This builds a stable cycle time.

* @return true if activated, false if it is activated (in use) already.

*/

static inline bool activateCycle_EventTaskTime_emC(EventTaskTime_emC_s* thiz, uint priority, int cycletime) {

if(thiz->prio.ctPriority == 0) {

ASSERT_emC(priority < mPrio_EventTask_emC, "priority faulty", 0, 0);

thiz->timeExec += cycletime;

thiz->prio.ctPriority = priority | mTime_EventTask_emC;

return true;

} else {

return false; // it is already activated.

}

}

This variant builds the new time stamp from the current last time stamp plus the cycle time. This allows to restart a task in a given cycle time independent of the execution time, which can be done in the task routine itself. Then only for the first call a delayed start or start with the absolute time is necessary.

That are the activating possibilities. The management of the tasks can now be programmed manually, but then the management which task should be start depending on the time and priority should also be programmed manually. The better way is, have a table of all tasks in the const memory (on FLASH on a simple controller) with some information, especially the start address of the task operation. Then a polling algorithm can test and evaluate all instances of task administrations and invoke the task with the highest priority if the time is expired.

The algorithm to do so is not complicated. It is presented and explained in the following text.

The const struct to manage a task is the following:

//file: src_emC/emC/Base/EventTask_emC.h:

/**Structure for const area (Flash, read only) for a given task.

* This structure contains a pointer to the task operation which should not able to destroy by any obscure software error.

* The associated event data are stored in RAM.

*/

typedef struct TaskConstData_emC_T {

/**It is for safetry check if the pointer to this const data are managed in data area. */

char const* signatureString;

/**The operation to call with the event. @noReflection */

TaskOperation_emC* operation;

/**data to use with the task operation. Can be null.

* In C programming only static data on a known memory address can be used here.

* This is also recommended for const in flash.

*/

ObjectJc volatile* thizData;

/**Reference to the event entry which may have current data for activating.

* It is necessary for polling over all given TaskConstData_emC instances. */

EventTask_emC_s volatile* const evEntry;

} TaskConstData_emC;

The signatureString needs one pointer position in the const area (Flash), it is a less effort

but it can help on software mistakes while developing:

The entry will be checked, only by comparison of the address of this pointer compared with one fix address

which contains any text. The text itself need not be checked, because it is in the const Flash Memory.

This helps if a pointer to this data is faulty in the user’s programming. If a pointer is faulty (any error), and the content is used to start a routine via function pointer, generally a faulty position can be used, with undefined behavior as result. This should be prevented. The effort is low, the probability of necessity is low, but the benefit to detect such an error is high.

The const data refers now to the task operation, to the data instance for the event,

and to a pointer to data in a universal, but also checkable form. A void* pointer is not checkable.

ObjectJc* has the capability to check the correctness of the data and its type, see ObjectJc_en.html.

If the data pointer is used, a task has always the same data.

But you can have the same taks operation with works with different data, may be proper and necessary.

You may have several such TaskConstData_emC dispersed in some modules or parts of the application.

To organize its execution as a whole, an array of references is necessary.

This array can be also organized in the const memory space (Flash) for a simple controller.

Of course in a dynamic system with changeable requirements it can be also existent in the RAM and changed on demand.

Such an array looks like:

TaskConstData_emC const* const evEntryArray[] =

{ &taskActivateShowLcd

, &taskHandleUartRx

};

only here with two entries. The routine which should be executed in the back loop to start the tasks is:

//file: src_emC/emC/Base/EventTask_emC.c:

void execPolling_EventTask_emC ( TaskConstData_emC const* const* evEntryArray, int nrofEntries) {

TaskConstData_emC const* entryAct = null;

int minPrio = 1;

int ix = nrofEntries;

//for(ix = 0; ix < nrofEntries; ++ix) {

while(--ix >=0) { // hint: Recommend loops count down as detecting zeros is easier instead ct up

TaskConstData_emC const* entry = evEntryArray[ix];

if(entry->signatureString != signatureString_TaskConstData_emC) {

THROW_s0n(IllegalArgumentException, "faulty TaskConstantData", (int)(intPTR)(entry), 0);

} else {

EventTask_emC_s volatile* entryData = entry->evEntry;

if( entryData->ctPriority >0

&& ( (entryData->ctPriority & mTime_EventTask_emC) ==0 // use without time

|| (timeShortStepCycle_emC() - ((EventTaskTime_emC_s*)entryData)->timeExec) >0

) ) { // OR time should be expired

if(entryData->ctPriority >= minPrio) {

entryAct = entry; // only a candidate for execution yet.

minPrio = entryData->ctPriority; // check only tasks furthermore with higher or equal prio

} // but increase the prio of all on each check

if(entryData->ctPriority <254) {

entryData->ctPriority +=1; //ct up priority, till it is the highest one

}

}

}

}

if(entryAct !=null) { //any task found to activate

EventTask_emC_s volatile* entryData = entryAct->evEntry;

entryData->ctPriority = 0; // reset the prio, is started.

entryAct->operation(entryAct); // call execution.

}

}

This routine regards both possibility with and without time. The distinction is done by the bit7 in the ctPriority, which forces using the inheritance data. Of course this should be correct. But if a software mistake is here (faulty bit set, though it is not a time event), then it reads faulty data for the time, no more, the error should be found.

As you see any time it is important to think about all possible mistakes in programming. The system should be stable anyway, even to support to find and fix the bug.

3.2. Using a message queue

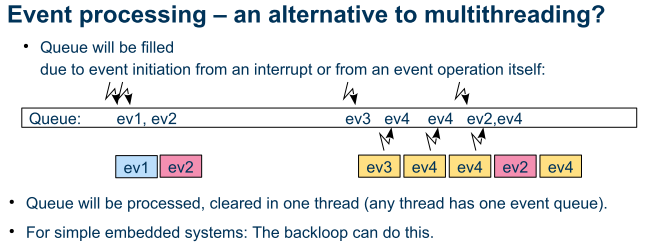

An event is the occurrence of the necessity to execute somewhat, in that meaning commonly known in information processing. An "event queue" is a false wording, events by itself cannot be queued. What is queued, it is a "message" to start an event. Hence the "event queue" is really a "message queue". This is often used in information processing.

The message queue is necessary espcially for working with state machines. For that the order of events is important.

The events are based on the same data structures as the EventTask_emC shown in the chapter above.

Look for details in the article about State Machines and Events: ../StateM/StateMEvQueue.html.

Such a state machine solution can be used also on cheep Controller platforms.

3.3. A small RTOS solution in the back loop

Though interrupts are immediately programmed with user’s code, a RTOS can run in the back loop. But often small processors are too less powerful for a complex RTOS. Any thread needs an extra stack, etc.

Because the power of the other solutions of embedded control (chapter above) are enough for many applications, and on the other hand RTOS systems are given and established, there is not an own solution in emC.

But the interface to different RTOS systems are clarified by the OSAL interface: ../OSHAL/OSAL.html